First post of 2026! This year my goal is to return to posting at least once per month (*fingers crossed*). This past August 2025 I returned to my role as Associate Professor of Spanish – and Director of Graduate Studies – after over 2 years as Interim Department Head, which was followed by a one year, long-awaited and postponed sabbatical (2024-2025). Since the fall, I’ve been enjoying teaching undergraduate classes again (especially my Almodóvar film class this semester), trying to preserve time for research and writing during the week, and continuing to plan and recruit students for this summer’s study abroad program in Spain — which will mark the 6th year (5th in a row!) that I’ll be taking students to Madrid and Pamplona for just over a month.

I thought I’d share what several students co-presented with me at the recent Kansas World Languages Association’s (KSWLA) annual conference in November, 2025. Each of these students had done exceptional work in Spain over the summer and I wanted them to be able to share their projects beyond our classroom – especially since we did not have a traditional classroom, of course! – and to showcase how Spanish language skills and Spanish study can enhance any other major. Our panel was titled “Beyond the Classroom, Beyond Tourism: Interdisciplinary Student Research in Short-Term Study Abroad (Spain),” and the goals were: (1) for students to share their research structures, on-the-ground activities, results, and reflections on linguistic, cultural, and professional growth, (2) to demonstrate how world language study can meaningfully intersect with STEM and other fields, and (3) to highlight language learning and continued language study as a pathway to global citizenship and intercultural competence, while also promoting creative models of student-centered research abroad.

I began the discussion sharing two opposing views of study abroad that have existed for decades and that are summarized in Student Learning Abroad. What Our Student Are Learning, What They’re Not, and what We Can Do About It (Vande Berg et al, 2012 & 2023). On the one hand, there is a [perhaps overly] optimistic and enthusiastic view that the experience is “naturally transformative” and students learn and grow simply by being in this new location, almost as if by some sort of “osmosis” (I’ve found this to be common with students’ expectations of “language immersion”). On the other hand, critics are more skeptical and may soberly argue that many programs amount to little more than tourism, or even a vacation from serious studies. The authors pointed to the below New Yorker cartoon, which I included to represent this view (below, right). I suspect that many familiar with student abroad (as faculty leaders or student participants) may have seen or experienced both of these sides! When I created this program, I wanted to try to strike a balance between formal learning and education… and the potential transformative power of students’ so-called “free-time” or unstructured explorations of their environment outside of official academic channels. This is where the individualized research component for my “Spain Today” course came in.

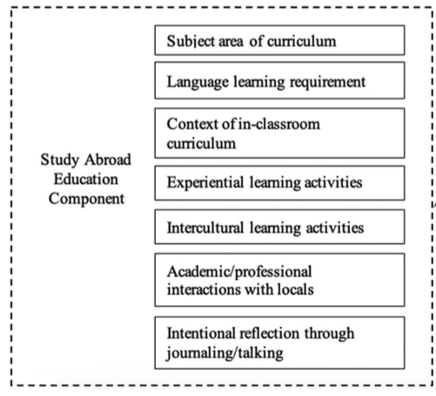

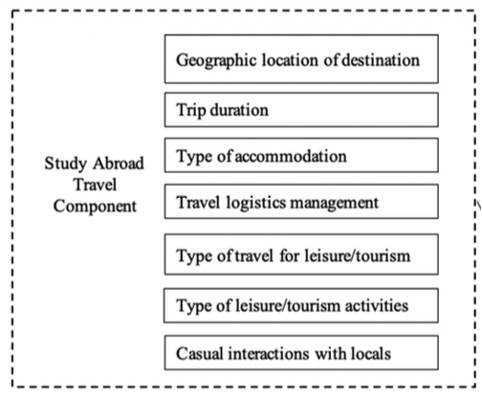

In “Education Travel and Personal Development: Deconstructing the Short-Term Study Abroad Experience” (2024), Dou, Fan, and Cai divided popular components of study abroad programs into “Travel” (tourism) and “Education” (academic) categories. This deconstruction is useful to me, as I’ve participated in programs that were less beneficial than others and, upon reflection, I believe it is the unstructured or unconscious fusion of these two components that may negatively impact learning and personal development or the overall success of a program (from a student point-of-view). Viewing each component within its respective category can help instructors more intentionally balance academic objectives and tourism/travel experiences, and ideally structure them in mutually beneficial ways. The authors note that not all travel experiences produce learning or personal development — which reflects the perspective offered by the New Yorker cartoon. They found that experiences in the “travel” category were only beneficial to learning when they were guided and intentional, or when students organized elements of the travel plans/logistics themselves (and short-term programs require minimal planning on the part of students)…. and unstructured sightseeing was one of the least effective experiences in terms of learning and growth. In the “education” category, the two most beneficial experiences were experiential, hands-on or interactive activities and academic or professional interactions with locals. These interactions, in fact, proved more beneficial than formal classroom study (even if characterized by “immersion”) and homestays (Duo et al, 335-86).

A well-designed research project is, at its core, experiential learning. But in the context of study abroad — especially short-term — it should also push students to interact with purpose and apply their Spanish language skills in real-world contexts. Research projects as part of study abroad have been shown “to facilitate a more intensive immersion into the local culture” (Streitwieser and Leephailbul 166), but meaningful engagement does not just happen spontaneously. I’ve found, over several years, that projects must by carefully planned before students step foot in Spain, and this starts with our on-campus meetings in March and April. Arriving in Spain with a research plan immediately gives purpose and structure to students’ interactions during their free time. Additionally, research has show that “only when immersion is combined with intervention int he form of cultural mentoring do most students learn and develop in meaningful ways” (Vande Berg et al 415). While immersion is often romanticized (as in the optimistic view above) and students often think that simply by living in another country they will absorb its language and culture, research tells us otherwise. Guided engagement or “intervention” on the part of the mentor or faculty leader is often essential to ensure a productive experience. I’ve learned this (and changed my thinking) over the years, as I initially thought maximizing student freedom and taking a more “hands-off” approach would give them more autonomy to explore on their own. However, in a short 3-4 week program, this can hinder student progress if they are unsure of where to begin, if they have even one negative interaction, or if something they intended to do is no longer possible upon arrival. Here is where we must recognize that learning in study abroad is “a dialogic and situated affair whose success depends not only on the student, but also on how they are received within their host community”(Kinginger 60; 67). No matter how motivated a student may be, many factors are simply beyond their control — locals may be too busy, the language barrier may feel higher than expected, access to certain spaces may be limited. In a faculty-led program, the instructor/mentor can help problem-solve in real time, and rather than distracting from an “authentic” experience (which had been my fear in the past), research shows that this “intervention” facilitates it, especially in short-term programs when time is precious.

The embedded research projects that form part of my study abroad program offer language majors the opportunity to connect their language skills to professional interests and academic areas of study that they typically only experience in English. Moreover, it offers language students the rare opportunity to make their work meaningful and visible, and even to earn funding. Language study is a field that many students (and administrators) do not readily associate with “research,” given that we don’t require labs, fancy equipment, rodents, or scary chemicals!! For this advanced Spanish course, each student designed and carried out an original project connecting Spanish language and culture to their primary field of study or their main areas of professional interest. The projects demonstrate the kinds of interdisciplinary learning and personal and linguistic growth than can happen when study abroad moves beyond both tourism or travel and the classroom, while also recognizing that “transformative” learning and personal growth occurs most readily when there is purpose, structure, and motivated engagement with the community and surrounding environment.

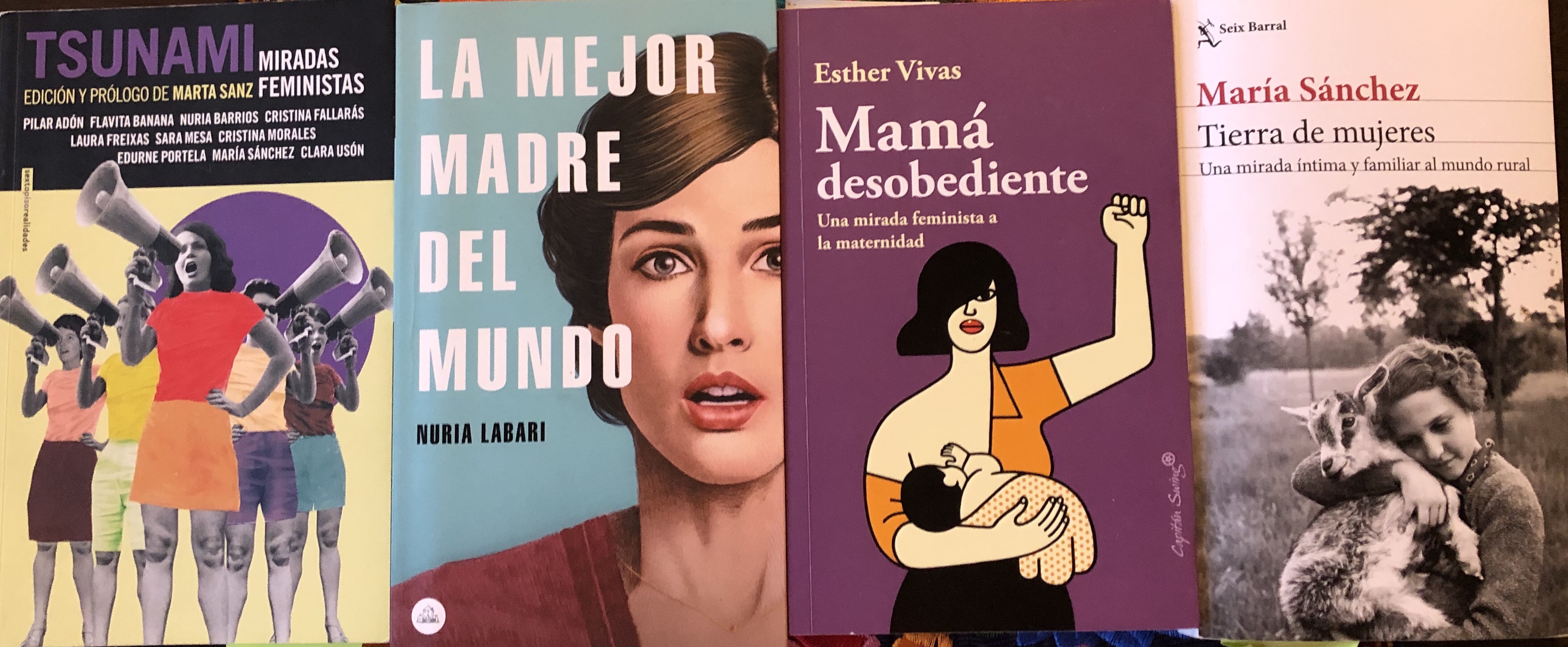

Below is a summary of each student’s research topic. At the end of this post you can access the full presentation via Google Slides (although without student explanations, of course!) and links to a few of the articles I referenced.

Laura Armbruster (’27) (top left) is a Spanish and Fine Arts major, and she declared her Spanish major right away upon enrolling in courses at K-State. She was interested in delving into the language/linguistic aspect of living in another country by examining the visibility/prevalence of multi- and bilingualism in Pamplona. She paid close attention to where she saw bilingual or non-Spanish materials in Pamplona and interviewed several shopkeepers, her professors, tour guides, and locals about their day-to-day language use (and needs) in her afternoon walks around the city. Rachel Gillam (’26) (top right) is a Psychology major who initially planned to minor in Spanish, but converted to a Spanish major after realizing she could complete 2 upper-level courses in the summer. For this course, Rachel chose to create a small-scale project in Spanish inspired by (and translated and adapted from) a study in the Psych Lab where she worked. As her survey dealt with somewhat sensitive topics about attitudes towards masculinity and child-rearing, she created a QR code link to her survey and spent her time introducing herself to locals and perfecting a 1-minute pitch in Spanish. She received over 60 responses.

Emma Hamilton (’26) (top left) has 3 majors – Agronomy, Entomology, & Spanish – and like Rachel, she converted her Spanish minor to a major shortly after taking a few courses at K-State and planning study abroad experiences (first in Chile, then Spain, and soon in Argentina!). For this course, she was able to integrate her Spanish skills directly into a research project that would build on her specialization in her main majors of Agronomy and Entomology, specifically looking at rural apiculture (bees!), as she is also a beekeeper in her home state of Wisconsin. She independently visited a rural apiary in the Ultzama Valley, and 3 other students went with her “for fun” (student field trip!), and she spent her free time after morning classes and on the weekends chatting with vendors at local markets; honey is an important local product in Pamplona and the Navarra region. Ashley Taylor (’27) (top right) is also an Entomology and Spanish major, who added Spanish as a second major after initially intending to minor. Ashely set the record for most interviews conducted, this year and in past years, with her well-designed, concise, and “attention-getting” survey that allowed her to talk to over 130 Spaniards about their attitudes towards and perceptions of insects. She also took time to seek out participants in every age group, talking to Spaniards ranging in age from 16 to mid-90s. She even learned about insects unique to the northern region of Spain, and we had to really dig to find out exactly what insect a Basque speaker in the Valle de Baztán was referring to!

Overall, this was great way for students to showcase their work beyond the classroom and even beyond the university, as KSWLA is attended by teachers and professionals across Kansas, Missouri, and the surrounding states. It also helped me further refine my approach to these projects and learn more about the research that has been done in this area so that I can continue to improve this individualized, high-engagement learning experience for students. I’m excited to see what projects students will come up with this summer – so far I know I have Spanish majors also studying Biochemistry (pre-med), Architecture, Horticulture, and Engineering… so we’ll be doing a lot of creative brainstorming this spring at our pre-departure meetings!

Below are the presentation slides (students’ “on-the-ground Research” slides are great!), the full abstract for our presentation, and a short bibliography of sources I explored in the framing of the projects and integrated research experience:

Presentation, via GoogleSlides – Student slides include: Project Structure, On-the-ground Research in Spain, Results, and Reflection.

Abstract: How can short-term study abroad program in world languages foster intercultural engagement, connect with students’ disciplinary interests, and advance language proficiency? This session presents a model for integrating individualized, small-scale research projects into a 4.5-week faculty-led program in Pamplona, Spain. Drawing on research that highlights the transformative potential of educational travel for personal and intellectual growth (Dou, Fan, & Cai, 2024), the program moves beyond both tourism and the traditional language classroom by engaging students in independent inquiry situated in their new global, but local, context. Student participants include majors in Agriculture, Health Sciences, Psychology, and the Fine Arts, who also pursue Spanish as a secondary major. Each designed and carried out an individualized research project in Spanish on themes such as masculinity, insect attitudes, culinary heritage, and bilingualism in public spaces. In this panel, student presenters will share their research structures, on-the-ground activities, results, and reflections on linguistic, cultural, and professional growth. Attendees will see how language study can meaningfully intersect with STEM and other fields. The session highlights language learning and continued language study as a pathway to global citizenship and intercultural competence, while also promoting creative models of student-centered research abroad.

Bibliography (select)

Dou, Xueting (Katherine), Alei Fan, and Liping A. Cai. “Education Travel and Personal Development: Deconstructing the Short-Term Study Abroad Experience.” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, vol. 36, no. 4, 2024, pp. 383-98. Full article: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10963758.2023.2192936

Goldstein, Susan B. “A Systematic Review of Short-Term Study Abroad Research Methodology and Intercultural Competence Outcomes.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, vol. 87, 2022, pp. 26-36. Link to PDF.

Kinginger, Celeste. “Enhancing Language Learning in Study Abroad.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, vol. 31, 2011, pp. 58-74. Doi: 10.1017/S0267190511000031.

Streitwieser, Bernhard and Robin Leephaibul. “Enhancing the Study Abroad Experience through Independent Research in Germany.” Die Unterrichtspraxis / Teaching German, vol. 40, no, 2, 2007, pp. 164-170. JSTOR: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20479958.

Vande Berg, Michael, R. Michael Paige, and Kris Hemming Lou, eds. Student Learning Abroad. What Our Students Are Learning, What They’re Not, and What We Can Do about It. Routledge, [2012] 2023. Proquest eBOOK: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ksu/detail.action?docID=987044