This semester at Kansas State I am teaching a survey course on Spanish Civilization and Culture. While it is certainly requiring me to brush up on history and politics (from prehistoric times to the present, nonetheless), it is also giving me a chance to more thoroughly explore some of my favorite Spanish artists with my students – particularly the works of Diego de Velázquez and Francisco de Goya. Between this week and last my class has been studying eighteenth century (Enlightenment) and nineteenth century Spain, and Goya serves as a perfect bridge between these eras – he was born in 1746, began painting for the Spanish monarchies in 1774, became official painter of the Spanish royal court in 1789, and continued painting almost until his death in 1828, though he lived his final years in exile in France. The subjects and themes of Goya’s paintings range from portraits of the Spanish royalty, to religion and the Inquisition, to provincial customs and traditions, to historical events capturing the horrors of the Spanish War of Independence in the early 19th century. In this post, I will discuss the question of authorship (paintership?) behind the Black Paintings, and also include some materials I created for a class activity – it’s been quite some time since I posted about class assignments or lesson plans, and this was a fun class that I thought was worth sharing.

“El quitasol” (The parasol) by Francisco de Goya (1777). Image via Wikipedia. High resolution image available via Museo del Prado: https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-parasol/a230a80f-a899-4535-9e90-ad883bd096c5

“El 2 de mayo 1808” (The 2nd of May, 1808) by Francisco de Goya (1814). Image via Wikipedia.

The Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, where the majority of Goya’s paintings are on display today, has organized Goya’s works in a fabulous online gallery, “Goya en El Prado.” Here, you can search paintings, drawings, prints, and even manuscripts, either by category or by date. The online presentation of the renowned “Pinturas negras” (“Black Paintings”) is exceptional, and I particularly appreciate the “Comparar” (compare) feature that allows you to evaluate two paintings of your choice side-by-side in a single window. You can view the entire collection of Black Paintings here via the Prado Museum. Below are two of my favorite examples – I am especially drawn to the dimensions of these two pieces, and also the interplay of light and dark that makes such an impact on these other wise “black” images.

Las parcas, o Atropos (The Fates). Image via Museo del Prado

La romería de San Isidro (The Pilgrimage to Saint Isidro). Image via Wikipedia

The Black Paintings – dated to 1820-1823 – are perhaps the most studied and, as I have recently learned, controversial of Goya’s oeuvre. These paintings clearly represent a dramatic shift in style, themes, and worldview, and they take their name as much from their dark appearance – the predominance of blacks and greys, as well as the limited light – as from their dark themes – terrible, pessimistic presentations of human suffering, illness, poverty, witchcraft, and nightmarish imagery. While these pieces have been given titles by art historians over the past century, they were not initially titled by Goya. In fact, they were not even discovered until well after the painter’s death in 1828 – they had apparently adorned the walls of his home in Madrid and were removed and transferred to canvas decades later, between 1873-74. The YouTube video below gives an excellent overview of Goya’s life and work (in Spanish) before concentrating predominantly on the Black paintings and the corresponding “transformation” of attitude and outlook that must have accompanied, or even inspired their production.

The video follows the common, rather melodramatic yet convincing narrative of Goya’s gradual disillusionment with the trajectory of both political and social progress. This narrative positions Goya on a path of decline, deterioration, and even bitterness by suggesting that he struggled with personal demons as he grew older – not only did he battle debilitating illnesses, one of which left him deaf, but he also witnessed the failure of Spain’s first constitution and the return of an oppressive, absolutist regime. The ominous music of the video underscores this notion, as does the sensationalist narration: “What happens when the artist comes face to face with misfortune? With the consequences of illness? … THIS HAPPENS!!!”. “THIS” meaning that he leaves behind the colorful, pleasant images of his early career and resorts instead to depicting the dark realities of his aging consciousness and ever more imminent death. Certainly, this is a plausible explanation for the contrast between paintings like these:

El pelele (The Puppet), Goya, 1791. Image via Wikipedia

Dos mujeres y un hombre (Two Women and a Man), Goya, 1821-1823. Image via Wikepedia.

However, the end of this particular video also alludes to recent investigations questioning the authenticity of these pieces. This part intrigued me, since I had not studied these paintings or their history in depth since my first visit to Spain over 10 years ago. I did a bit more googling research and promptly came across a 2003 article in the New York Times, The Secret of the Black Paintings. In the process of writing a book on Goya and the Black Paintings, professor and Art historian Juan José Junquera (Complutense University, Madrid) conducted research not only on Goya’s life and artistic production, but on the home within which the paintings were found. The entire NYTimes article is worth reading for the details of this fascinating archival investigation, but I’ll briefly summarize the evidence that Junquera suggests might cause us to reexamine the attribution of these paintings to Goya. In sum, Junquera examined the deeds of sale for Goya’s property (La Quinta del Sordo) – he found that when Goya sold the property, it was only a one-story dwelling. The second story – which contained several Black Paintings – had apparently not been added until after Goya’s death! It is possible then, according to Junquera, that Goya’s son painted the notoriously grim images, and that they were subsequently brought to public attention by Goya’s grandson who, needing money, knew he could receive more for paintings purportedly created by his famous grandfather than by his father. You can see a virtual reconstruction of the Black Paintings’ locations within the Quinta del Sordo here.

Peregrinación a la Fuente de San Isidro, o El Santo Oficio (Pilgrimage to the Fountain of Saint Isidro, or The Holy Office). Image via Wikipedia

In my class we discussed the changing themes of Goya’s art over time, particularly in terms of his modern renditions of war (El dos de mayo, El tres de mayo), his haunting and often satirical etchings, and the Black Paintings. But we did not delve into the question of authorship – I’m planning to return to this concept towards the end of the course s we discuss Contemporary Spain. This will also give me more time to read more about these recent discoveries and theories. Instead, I had the class work in small groups to analyze select paintings by Goya that related most directly to the historical content of the course – I used “La familia de Carlos IV” (Charles’ IV’s Family), “Fernando VII en manto real” (Ferdinand VII in Royal Robes), “El tres de mayo 1808” (The 3rd of May, 1808), and two select etchings dealing with the Inquisition and Women. I am attaching PDF documents at the end of this post – one with the images I used, one with the questions that I gave to each group, and one with “fun” coloring-book images that I used for the fifth part of the activity.

image via Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/289426713529351509/

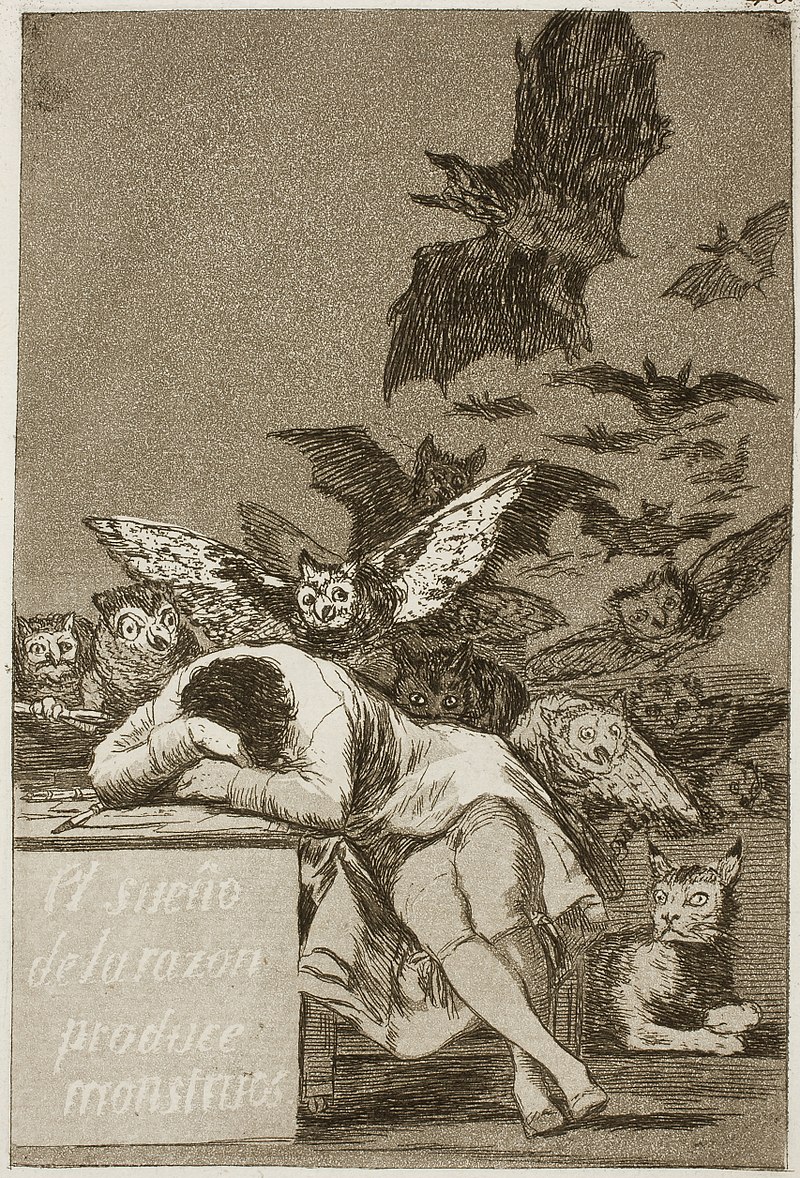

After discussing the homework, which consisted of Goya’s etching “El sueño de la razon produce monstruos” (The sleep/dream of reason produces monsters), I divided my students into 5 groups of 3 and 4 each. I gave everyone the “questions-Tasks” document, which contained one or two questions for each of the four images I handed out. I gave one image each to four groups… and the fifth group got crayons and the coloring-pages. For 8-10 minutes they analyzed and discussed their assigned painting and its accompanying questions (or they colored!). Then, I collected the images and re-distributed them. I’m sure a few students wondered why their college professor was giving them crayons and a “coloring book”, but at this point in the semester a bit of stress-relief is always appreciated – for both professors and students. In fact, I felt guilty taking the crayons away from them when their coloring turn was over! In any case, the following class we discussed each group’s thoughts on these paintings, the majority of which also served to “introduce” the main events of the early nineteenth century (Charles IV, Spanish War of Independence, Ferdinand VII).

El sueño de la razon produce monstruos (The Sleep/Dream of Reason Produces Monsters) 797-99. Image via Wikipedia

I’m looking forward to revisiting Goya in a few weeks to further discuss questions of authorship, authenticity, and cultural narratives. If any of my readers are or have taught a Spanish Culture course, I’d love to hear your thoughts on resources and productive assignments. What types of activities have you used to break up what can easily become monotonous presentations of historical facts? Do you incorporate projects that are not writing intensive in upper level Spanish courses?

Resources:

For groupwork (groups of 3-4 are ideal):

Discussion questions and writing tasks: Goya_questions-Tasks

Paintings to accompany questions/tasks: Goya_paintings for discussion

College coloring fun: Goya_coloring

Pingback: Walking Around Scarecrows and Scarefishes: Surrealist Angst in Maruja Mallo and Pablo Neruda | Rebecca M. Bender, PhD