I have officially decided that September is the fastest-moving, shortest month of the (academic) year. It flies by quicker than winter break. One day you are rather calmly introducing the course syllabus and getting to know new students… the next you are grading essays and the first round of chapter exams, creating midterm exam and project prompts, and counting down the days until fall break. Who assigns all this student-work anyway?!?

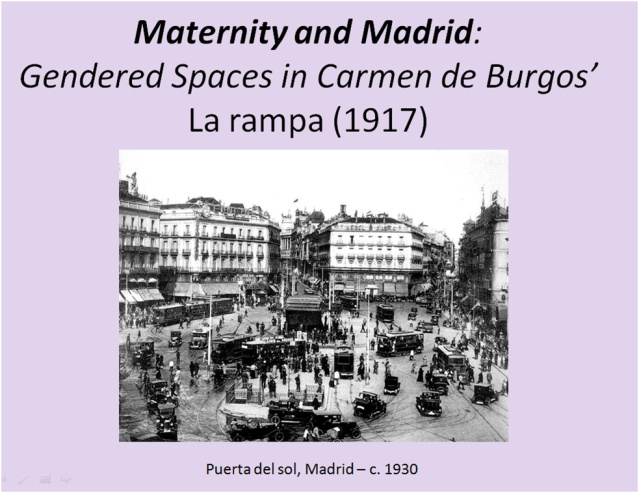

In addition to teaching my three classes, I had volunteered to present at one of Grinnell’s European Studies Salons this semester. This past Thursday evening was the first in a series of three “Salons” this fall hosted by Grinnell College’s European Studies Concentration. The events are intended to promote the college’s European Studies Concentration while allowing students and faculty to share and discuss their academic research projects in relaxed, non-academic settings. The promotional fliers on campus describe the Salons as “social gatherings for the informal exchange of ideas with food, drink, and good cheer.” The first salon, for example, was hosted by Professor Kelly Maynard (History), and the theme was “Sex and the City”. For a new initiative, we had an excellent turnout of more than 30 professors and students which, to be honest, was actually a larger audience than I have faced at many professional conferences! I think it was the allure of “food and drink,” combined with the enticing topic of “sex and the city”. I presented a portion of my research on the representation of specifically gendered city spaces – notably Madrid’s maternity ward – in Carmen de Burgos’ 1917 novel La rampa; Kristina Kosnick, lecturer in the Department of French and Arabic, presented on narrative strategies used by protagonists in contemporary francophone texts to relate their bodies to the urban cities that surround them; and Dana Sly, a senior Art and Art History major at Grinnell (’15), discussed the research she conducted last semester on women in the Sherlock Holmes series.

While La rampa and the maternity ward form a portion of the second chapter of my current book project, and I have written a relatively lengthy article on this topic, I approached that argument largely with regards to how the female protagonist and her pregnancy functioned didactically as a means of educating (warning?) women of the potential risks and pitfalls of motherhood (in general, such “negative” depictions of pregnancy and motherhood were uncommon at this time). My women’s literature course also read an abridged version of La rampa last semester, and I discussed their projects on female identity here. But for this short, informal presentation, I re-framed my analysis to concentrate on the gendered nature of the maternity ward as an enclosed space within Urban Madrid – within this unique setting, readers encounter varied female experiences that are conspicuously absent from canonical male-authored narratives dealing with life in Madrid at the height of modernity. Isabel’s experience in La rampa does not fit within the image of Madrid as a bustling, metropolitan city full of new opportunities (like the picture above), which is often presented by male writers during the same time period. On the contrary, Burgos’ novel opens with a heartfelt, rather ominous dedication to her female readers:

“To the multitude of defenseless, disoriented women who have come to me, asking me what path they should take, and who have caused me to lament their tragedies” (1).

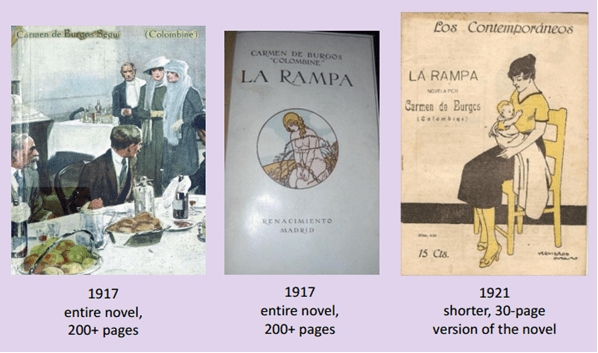

According to the newest edition of “La rampa” (Stockcero 2006), this cover graced the earliest editions of the novel.

From the onset, readers can deduce that their protagonist will face challenges and setbacks in her quest to improve her lifestyle in the city. To briefly summarize La rampa, Burgos portrays the life experience of Isabel, a single, formerly middle-class woman struggling to support herself in Madrid. She works as a shopgirl in the centrally located Bazar, but when she discovers she is pregnant her life takes a dramatic turn. Due to increasing physical limitations, Isabel must give up her job and, as a result of losing her only source of income, she seeks out Madrid’s charitable maternity hospital, la Casa de Maternidad.

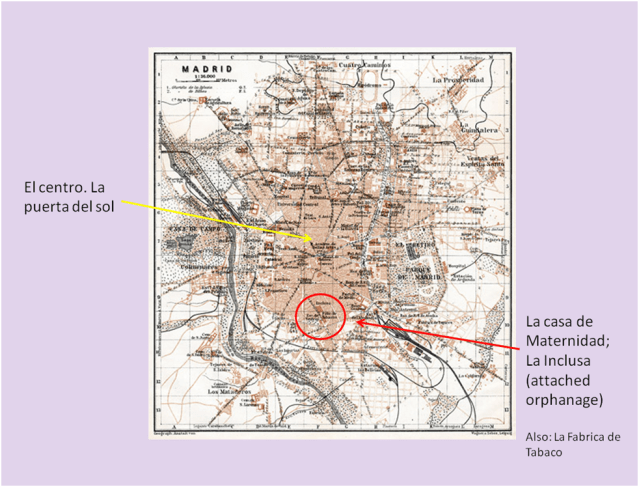

I limited my discussion to two main elements: (1) the geographic location of the maternity ward and (2) how experiencing pregnancy in this location affected women’s sense of self. First, the precise geographic location of the Casa de Maternidad within Madrid is especially relevant to an analysis of gendered spaces within the capital. According to the novel, along with the Hospital General, the open-air flea market El Rastro, and the Tobacco Factory, the Casa de Maternidad and the attached orphanage (the Inclusa) were strategically grouped together, just outside the increasingly modern city center. The peripheral location of the maternity ward thus obscured both the unpleasant aspects of pregnancy, as well as the consequences of what were considered immoral sexual relations. As the protagonist approaches the doors of the maternity ward, she fixes her gaze upon its looming presence:

“It seemed that they had grouped everything together in this neighborhood in order to clean the golden city center of its miseries – the same way that they cast the dead far away, in the outskirts of the city, so that the view of the Cemetery and its putrid emanations do not trouble or contaminate the city’s inhabitants” (103).

Given that the Casa de Maternidad depicted in the novel was an actual institution that existed in 1920s Madrid (near the neighborhood of what is today Lavapies), I thought a map depicting the city at this time would be useful for illustrating the citation I selected from the novel. At The 1900 Collection, I discovered several old maps and plans of Madrid from between 1899-1929 – high-resolution copies can be purchased for about 13 euros. Below is a low resolution copy of the image I selected from 1899 (the novel takes place in 1917):

Map of Madrid during the 1920s. You can access a larger version of the map here: http://www.discusmedia.com/catalog.php?catId=9.1.12

This map provides an important visual of the location of the Casa de Maternidad in relation to the areas of the city most frequently discussed and presented in both literary and cultural history accounts of Madrid at this time. To discuss this space, I referred to Michel Foucault’s concept of the heterotopia, though I simplified it significantly for an audience composed of undergraduate students from many different fields of study (including biology, political science, philosophy, and languages). There is a link to Foucault’s article at the end of this post, and you can view my PowerPoint presentation and paper to read my interpretation of the ward through this principle. The main point I wanted to emphasize was the way in which this city space functioned as a means of identifying and isolating a specific portion of the female population – single mothers. By way of this “heterotopic” spatial isolation, single mothers in this ward represented an immoral deviation from the traditional norm of female pre-marital chastity. Even more importantly, this was a gendered transgression, as no men occupied this institution, nor did a parallel space exist for sexually “immoral” males.

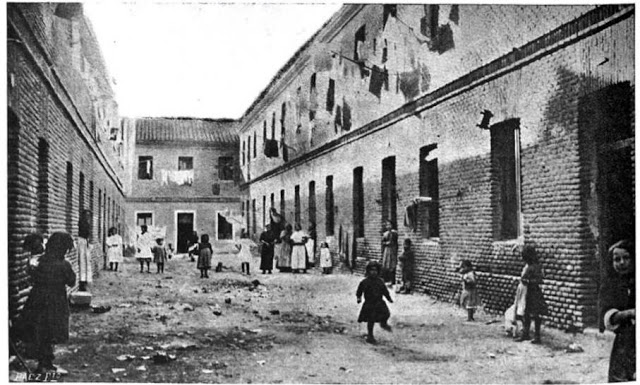

Casa de Cuna, Cadiz (Spain). I have been having difficulty locating images of Madrid’s Casa de Maternidad. This image depicts the interior of the Casa de Cuna in Cadiz, and institution run by Catholic Nuns that would take in abandoned infants and children. See the link for its fascinating history.

Of equal importance is the fact that La rampa provides a counter-discourse to official historical records. While the website of Madrid’s Hospital General Universitario refers to the “Historia del Hospital Materno Infantil,” it provides little insight into the actual experience of women in the institution at various points in history. For example, when discussing the place of the ward within the city, the website explains that in the late nineteenth-century, “the hospital’s fame and prestige had extended throughout all of Madrid.” Certainly there is truth to this statement; a hospital of this size at the turn of the century was indeed an admirable display of science, medicine, and progress. However, the details Burgos includes in her novel indicate that female patients were certainly not benefiting from nor celebrating this institution’s “fame” or “prestige”. On the contrary, they suffered greatly within the walls of the ward and were mistreated by the nuns who worked there. Below are a few examples of the way in which Burgos incorporates the medical language of progress into a decidedly non-progressive depiction of the female experience in this space.

- As she enters the main room of the Casa de Maternidad, the narrator describes Isabel’s impressions of her new peer group: “…that group, formed of about fifty withered, haggard women who appeared tired of supporting their dropsical abdomens… Some of them were married women who, lacking proper medical care, found themselves there; but the majority were single women, the deceived, the abandoned. There were old women, repeat offenders who had already left several children there, who only saw their maternity as an unpleasant physical accident, purely mechanical, from which it was necessary to escape as if it were typhus or pneumonia, without any sort of sentimentality” (108).

- Pregnancy is described as an illness, show to attack and disable the female body; Isabel fails to recognize herself upon catching a glimpse of her reflection prior to entering the Casa de Maternidad: “Was she really that flaccid woman, with swollen features even despite her emaciation; with a tired face, fallen; cheeks covered by a yellowish tinge that seemed to cover her eyes, giving her that peculiar expression of pregnant woman; that opaque look that appears to convert their pupils into the crystals of glasses through which they wish to see other eyes?” (104).

- In La rampa, women are not happily awaiting the birth of a beautiful new baby, but rather suffering from an illness provoked by the “polyp, fetus, garbage, illness, stain, or tumor stirring within their wombs” (123-27). The words child, son, daughter or baby (hijo/a, niño/a, bebé) are virtually absent from the chapters dedicated to the Casa de Maternidad, effectively dehumanizing and devaluing the maternal experience within the walls of this institution.

All of the above translations are my own and, to be honest, translating the Spanish to English was quite eye-opening – I felt the force of the language even more profoundly when attempting to find English equivalents. Also, I had never used the word dropsical before, and I always appreciate “learning” English while studying Spanish!

Conditions in which children lived and played in early 20th century Madrid. The Casa de Maternidad and the attached Inclusa took in abandoned children, however they discouraged women from leaving their children in the institution after giving birth due to the very little space available. (Foto: Páez, 1914; Memoria de Madrid. Taken from: http://laventanadeteresa.blogspot.com/2012/05/la-maternidad-2-parte.html)

As this post has gotten a bit long, I will not go into more detail about the second main aspect of my presentation (how experiencing pregnancy in this location affected women’s sense of self, using Julia Kristeva’s notion of the abject), but you can access my short English paper at the end of this post if you’re interested in learning more. I also want to make it clear that I am in no way attempting to endorse Burgos’ fictional narrative as an historically accurate depiction of pregnancy in Madrid at this time; I do, however, believe literature provides us with another window through which to view history, and therefore even fictional accounts contain relevant information about the past. I will end this post here with the slide I also used to wrap up my presentation – three different covers that were used to illustrate La rampa at three different moments. What you you think about these different depictions of the novel? If you have read La rampa, which do you think is most accurate? Misleading? Perhaps inappropriate? I would enjoy your comments of feedback, especially if you have used the novel in a Spanish literature course.

Resources:

Bender, Rebecca M.

(paper) “Maternity in Madrid: Gendered Spaces in Carmen de Burgos’ La rampa (1917)”

(PowerPoint) “Maternity in Madrid: Gendered Spaces”

Burgos, Carmen de. La rampa, ed. Susan Larson. Buenos Aires: Stockcero, 2006. Print.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces.” Trans. Jay Miskowiec. Diacritics 16.1 (1986): 22-27. Print. JSTOR: http://www.jstor.org/stable/464648. PDF available online here.

“Historia del Hospital Materno Infantil.” Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Comunidad de Madrid. 2002. Web. 7 Sept. 2010. <http://www.madrid.org/cs/Satellite?cid=1142588696022&language=es&pagename=HospitalGregorioMaranon%2FPage%2FHGMA_contenidoFinal>.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror. An Essay on Abjection. Trans. Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia U P, 1982. Print.

Ugarte, Michael. Madrid 1900: The Capital as Cradle of Literature and Culture. University Park: Pennsylvania State U P, 1996. Print.

Versluysen, Margaret Connor. “Midwives, medical men and ‘poor women labouring of child’: lying-in hospitals in eighteenth century London.” Women, Health and Reproduction. Ed. Helen Roberts. Boston: Routledge, 1981. 18-49. Print.

![A pittilesse Mother. That most unnaturally at one time murthe[red] two of her owne Children at Acton ... uppon holy thursday last 1616, the ninth of May. Beeing a gentlewoman named M. Vincent ... With her Examination, Confession and true discovery of all t[he] proceedings ... Whereunto is added Andersons Repentance w[ho] was executed ... the 18 of May 16[16].](https://rebeccambender.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/infanticide_1616.jpg?w=640&h=567)