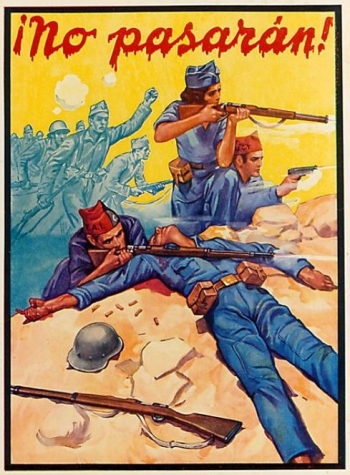

A few weeks ago one of my friends passed on a link to these Spanish Civil War posters, which were published over at Retronaut, “The Photographic Time Machine.” I had just finished teaching a unit on representations of the war in film (El laberinto del fauno), theater (Escuadra hacia la muerte), and art (Picasso and Dali) so this was a timely find.

Since there was no text accompanying this particular “photo-blog” entry, I wanted to do a bit more investigation. The post linked to the Spanish National Library (Biblioteca Nacional de España) and the images contain their copyright, but I was unable to find these exact images at the library’s website. I did, however, find an extremely detailed online exhibit curated by the University of California, San Diego: The Visual Front. Posters of the Spanish Civil War. The site contains a chronology of the war, an introduction to the history and power of images used in revolution and war (by Alexander Vergara), and a visual index of nearly 100 Spanish Civil War posters. From the visual index page, you can click on each thumbnail to learn more about each specific poster; details include English translations, sponsors and distribution, and a general overview of the social, political, and cultural context that informed each visual.

UCSD’s online exhibit, “Visual Front,” contains only a sample of the numerous poster created during this time period – according to the introduction, about 1,500 to 2,000 unique posters were designed during the war years (1936-39), and about 2,000-3,000 editions of each were printed. In this post you will find a sample of the propaganda posters and information available over at the UCSD exhibit. Since I ended up finding such an enormous variety of posters from various websites as a result of my online investigation [links below], I am planning to do a follow-up post with a more focused analysis of repeated themes and imagery – given my current research interests, it will likely focus on the way in which gender (masculinity and femininity) and the family (mothers, fathers, children) are deployed to communicate a range of messages regarding nationalism and Spanish patriotism.

Below is the first poster that caught my attention – produced by the anarcho-syndicalist trade union, the CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, or National Confederation of Labor). Here, as the UCSD summary explains, “the Spanish conflict is presented as the struggle of man against beast.” It was designed by the artist and graphic designer Manuel Monleón (1904-76), who specialized in techniques of photo-montage. This poster is likely from the early months of the Civil War in 1936.

In the next poster below, “Mañana el mundo, hoy España / Tomorrow the world, today Spain”, I was drawn to the juxtaposition of a smiling baby, Hitler, and Paris – three elements that scream political propaganda if there ever were any! Here, the Spanish conflict is placed within a lager scale, suggesting that Spain may become “the gateway to the spread of fascism across Europe and the ‘world’.”

Tomorrow the world, today Spain. [Source: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/visfront/newadd27.html%5D

Finally, a third poster that interested me was one of the few in the UCSD collection that featured female figures: “Que tu familia no viva el drama de la guerra: Evacuar Madrid es ayudar a la victoria final / Don’t let your family live the drama of the war: To evacuate Madrid is to help the final victory.” According to the summary, “this poster was distributed between mid-December 1936, when the government of Madrid began its intensive effort to evacuate the city, and April 1937, when the issuing entity was dissolved.” Evacuating the city was considered essential to avoid increased civilian casualties and, while many citizens had indeed fled to safety in other regions of Spain, the exodus slowed down by late December. This poster attempts to show the dangers of living in the city – not only was the threat of enemy bombers greater, but provisions and secure housing were becoming scarcer. And of course, what better way to convey this danger than to depict the terror faced by women and children?

Take some time to visit the links below – While I selected a few posters from UCSD’s “Visual Front” exhibit, I actually think there are more curious, visually appealing posters on a few of the sites linked below. Which images would you like to explore further? Do you know of other useful online resources that I have not included here?Resources:

Edelmen, Lee. “The Future is Kid Stuff. Queer Theory, Disidentification, and the Death Drive.” Narrative 6.1 (1998): 18-30. JSTOR: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20107133

The Visual Front: Posters of the Spanish Civil War. University of California, San Diego’s Southworth Collection, which I referenced and relied heavily upon for this post. Introduction by Alexander Vergara.

Digital Poster Collection: Spanish Civil War (1936-39). Here you can view posters from a variety of political and cultural contexts: Spain’s Republican and Nationalist Factions, France, and Germany.

Library of Congress: Spanish Civil War posters: The Library of Congress’ collection contains approximately 120 posters. You can click on the thumbnails to access JPEG files, and very basic information is provided for each poster (date created/published, titles and translations, and the creator, sponsor, or advertiser). Unlike the UCSD’s “The Visual Front” exhibit, there is no narrative description or background information provided.

Retronaut: Posters from the Spanish Civil War. These images are extremely colorful and among the most compelling visually, however there is no information provided about any of the posters.

Pingback: The Memory of War in Madrid | Rebecca M. Bender, PhD

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.

Pingback: Picasso’s “Guernica” and Aleixandre’s “Oda”: The Spanish Civil War in Art and Poetry | Rebecca M. Bender, PhD

Pingback: Teaching “La hija del sastre” | Señora G