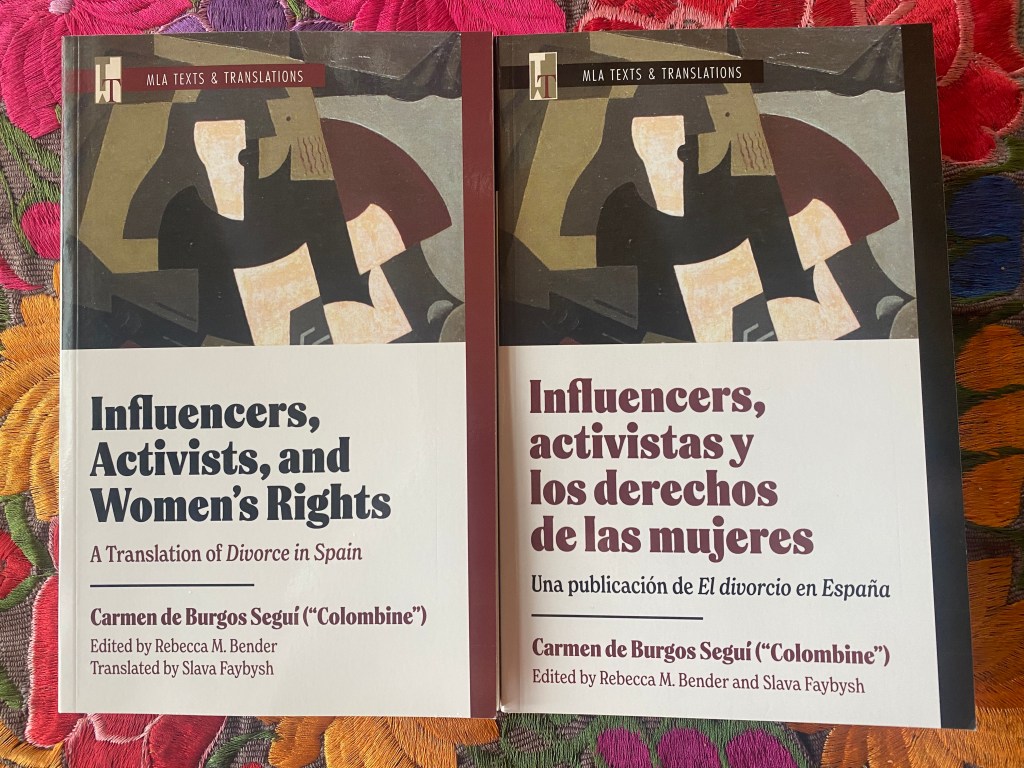

This week, in addition to starting my long-awaited sabbatical (yay!), I was excited to receive my copies of the companion volumes of the English translation and a new Spanish edition of Carmen de Burgos’s El divorcio en España (1904). I wrote the introduction to both volumes and worked with the translator, Slava Faybysh, on the editing. Slava did an enormous amount of work on the entire translation and the footnotes, and I worked with him to expand and revise the footnotes and ancillary materials of each text. The English Translation volume is Influencers, Activists, and Women’s Rights: A Translation of Divorce in Spain, and the Spanish edition is Influencers, activistas y los derechos de las mujeres: Una publicación de ‘El divorcio en España.’ Together, both texts capture the historic debate on divorce in early 20th-century Spain, a key moment in the country’s very early feminist movement. The English translation makes the diversity of Spanish opinion on the matter available to non-Spanish speakers. Both volumes were published this August (paperback) and September (eBooks via Kindle, Nook, Apple) by the Modern Language Association (MLA) in the Texts and Translation Series.

Below I’ll excerpt a bit of my introduction, which is directed at a general audience and undergraduate students who may have limited to no knowledge of Carmen de Burgos or the early women’s movement in Spain. I wrote it framing Carmen de Burgos as a sort of early 20th-century “influencer,” hence the title of the volumes.

Divorce in Spain is the result of one of her first initiatives as a columnist for the Diario Universal, one of Madrid’s most prestigious, liberal-leaning newspapers in the early twentieth century. This book-length publication, translated to English for the first time here, is the result of a survey that Burgos published in late 1903, calling for editorials reflecting her readers’ opinions on divorce. After receiving hundreds of responses, she compiled several from high profile individuals and published them together as Divorce in Spain in 1904. This early publication is unique in terms of Burgos’s literary output, as she did not write the full text herself, but rather compiled the writings of others, edited them into a cohesive volume, and added her own introduction and commentary. Divorce in Spain reflects the Spanish public’s opinions on the definition and purpose of divorce in Spain’s legal codes, but it also contains a contribution from Burgos herself, in which she argues in support of divorce reform. Her clever essay, “The Divorce of Nuns,” cheekily proposes that, if Catholic nuns could renounce their vows and divorce the most perfect of all “husbands” (Jesus Christ), then Spanish women should certainly be permitted to divorce their mortal, imperfect husbands. As a result of her brave initiative, Divorce in Spain prompted public debate on a contentious topic related to the early women’s movement and played a pivotal role in the eventual legalization of divorce in the 1930s, although this victory that was later rolled back during Franco’s dictatorship (1939-75).

[… After Burgos left her husband and their rural Almerian village, she] relocated to Madrid in August of 1901, established contact with the intellectual world, and developed professional relationships with some of Madrid’s top journals and newspapers. […] By 1903 she began publishing a regular column, “Readings for Women,” in the prestigious Diario Universal. It was the director of this newspaper who gave her the pseudonym “Colombine,” a playful namesake that she would retain throughout her career, not to hide her identity, but rather to appeal to working-class readers (Kirkpatrick 172). In a sense, we might say that Burgos took to early 20th-century Madrid and its far-reaching print media like 21st-century influencers take to Los Angeles or New York to deploy the power of their identities and brands through popular media like Instagram, YouTube, or TikTok. Her control over “Readings for Women” gave her access to a large audience of predominantly female readers. Her role as editor afforded her a degree of authority, while her knowledge, personal experiences, professional position, and carefully cultivated relationship with her audience granted her a uniquely modern influence over her readers’ opinions. As a writer and journalist, she frequented the most exclusive, male-dominated intellectual and avant-garde circles of her time, even establishing her own popular social-gathering (tertulia) in Madrid in 1906, “Colombine’s Wednesdays.” Like today’s influencers, Burgos aimed to engage her audience by publishing hot-button content that would raise awareness and prompt discussions on evolving social or cultural issues.

This was the case with divorce, and Burgos in late 1903 began surveying her regular readers, or “followers,” and suggested that a “Club of Unhappily Married Couples” be formed in Madrid to study the Spanish divorce laws and present an argument for their reform in parliament. She immediately received letters supporting this endeavor, and the swift replies prompted her to launch a poll requesting the opinions of her readership and of Spain’s most eminent literary and political personalities. Among the most prominent intellectuals who responded were the novelist, poet, and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno; the novelist Pío Baroja; and early feminist novelist and essayist Emilia Pardo Bazán. As high-profile responses to her query continued to arrive over the following months, she selected contributions to publish weekly in the Diario Universal, then compiled them into a cohesive volume published as Divorce in Spain in 1904. This ongoing project on divorce was enormously popular and, not surprisingly, controversial. In publicizing and promoting debate on divorce, Burgos “manifested a lack of respect for and adherence to the Catholic Church, a cornerstone of middle-class Spanish women’s existence and the public expression of their moral character” (Bermúdez & Johnson 178). Consequently, she earned a new nickname, “the Divorcer,” which was pejoratively used to challenge her authority and mire her reputation. Today we might say that this hashtag-worthy moniker was deployed in a failed attempt to “cancel” her, or to discredit her arguments and stifle her ambitions.

You can read my full introduction to Divorce in Spain / El divorcio en España — covering Carmen de Burgos and her relationship to early Spanish feminism, as well as the status and definitions of divorce and separation in the Spanish legal codes — in either the English translation volume or the Spanish edition. They’re both available via the MLA bookstore below. You can also email me if you’d like a copy of the introduction, or access it via my Academia page.

The original Spanish version of El divorcio en España, published in 1904, is available online, open access in PDF format, via the Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

Both volumes can be purchased from the MLA Bookstore. Members receive 30% off; and other readers can obtain a 20% discount with the code MLA20.

- Purchase the English Translation here: Influencers, Activists, and Women’s Rights: A Translation of Divorce in Spain

- Purchase the new Spanish edition here: Influencers, activistas y los derechos de las mujeres: Una publicación de El divorcio en España